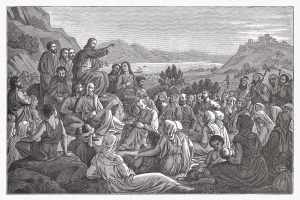

When I relocated to Texas in 1996, I was acquainted with only one Jesus, the Jesus of the Sermon on the Mount. This Jesus, whether historical or mythological, left an indelible mark, significantly shaping my worldview and values.

Christ was a figure of peace, humility and radical love for me. This Jesus preached turning the other cheek, loving one’s enemies and the blessedness of the meek.

In Matthew 19:24, Jesus said: “It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God.”

To me, this meant that to enter the Kingdom of Heaven, greed and selfishness could not exist. Jesus called for faith to be lived out in personal acts of kindness and humility.

Then, I moved to Texas and met a Jesus utterly foreign to the one I had grown up with and knew. Who was this strange Jesus? One quote from Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount kept running through my head. “Beware of false prophets which come to you in sheep’s clothing, but inwardly they are ravening wolves. Ye shall know them by their fruits.”

I had no idea that in American Christianity, two distinct portrayals of Jesus emerge from the New Testament. On the one hand is the Jesus of the Sermon on the Mount. This Jesus is a teacher of profound ethical and spiritual wisdom, calling his followers to a higher standard of living that encompasses not just love and peace, but also justice, humility, integrity and a deep trust in God.

On the other hand, the Jesus of the Book of Revelation embodies divine judgment, authority and power, often depicted in a manner that contrasts sharply with the more peaceful and compassionate Jesus of the Sermon on the Mount.

In Revelation, Jesus is the ultimate judge of humanity, dispensing wrath upon those who have defied God. His role as the executor of divine justice is central, a justice portrayed in violent, apocalyptic terms. He comes with a sword, ready to strike down nations, his judgment final and absolute.

The Jesus of Revelation is portrayed as the King of Kings and Lord of Lords, a title that emphasizes his supreme authority over all earthly powers. There is no room for dissent or disagreement — his word is law, and his decrees are carried out with an iron hand. This unyielding authority can be arrogant, as he demands total submission and loyalty from all creation.

Anger is a significant aspect of this depiction. The Jesus of Revelation is often filled with righteous indignation toward sin and rebellion. His anger is not merely a passing emotion but a driving force behind the cataclysmic events described in the book. His wrath pours out through plagues, wars and destruction, showing no mercy to those who stand against him.

This Jesus is also an avenger, particularly of the martyrs and the faithful who have suffered for their beliefs. He is determined to vindicate them, often through acts of vengeance against those seen as oppressors. This vengeful aspect of his character is a far cry from the forgiving Jesus of the Gospels, highlighting a more militant and aggressive side.

In Revelation, Jesus is depicted as a warrior leading the armies of heaven in a final, apocalyptic battle against the forces of evil. He tramples his enemies underfoot, an arrogant assumption of inevitable victory and domination. This Jesus is neither meek nor mild; he is aggressive, assertive and forceful.

The Jesus of Revelation is also a destroyer, particularly of the wicked and the corrupt. His anger toward the sinful world culminates in the destruction of Babylon, a symbol of human depravity. This destruction is thorough and relentless, reflecting a Jesus who is not just angry, but vengeful and determined in his pursuit of perceived justice.

In Revelation, Jesus asserts his identity as the Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the end, underscoring his eternal sovereignty and unmatched power. This self-identification can be seen as a form of divine arrogance, as it places him beyond all questioning and above all creation.

Unlike the Jesus of the Gospels, who invites followers, the Jesus of Revelation demands worship and allegiance. There is a stark dichotomy between those who follow him and those who do not, and the consequences of refusal are severe. This insistence on absolute loyalty, combined with the severe penalties for noncompliance, adds to the image of a Jesus who is both arrogant and authoritarian. For this Jesus, liberty of conscience is sinful.

Various Christian groups have interpreted and emphasized these two depictions of Jesus differently. Each interpretation has profound implications for the relationship between church and state in America, and the weight of this cannot be overstated.

The Jesus of the Sermon on the Mount represents a vision of Christianity that aligns with the principles of separation of church and state. His teachings emphasize personal virtue, compassion and a clear distinction between the spiritual and the temporal.

This Jesus calls for a daily faith lived with compassion and kindness rather than one that seeks to impose itself through government machinery. His message supports a secular state where religious belief is a matter of individual conscience, not coercion.

In contrast, the Jesus of Revelation has been seized upon by those envisioning a Christian nation that entwines religious authority and governmental power. This Jesus is a conqueror, a judge, a king who demands allegiance not just in the spiritual realm, but also in the worldly one.

For those who promote the idea of America as a Christian nation, the Jesus of the biblical End Times offers a justification for merging church and state, arguing that actual governance must be rooted in Biblical authority and that secularism is a threat to the divine order.

The tension between these two images of Jesus is at the heart of the ongoing debate over the role of religion in American public life.

The key Founders of this nation, sons of the Enlightenment and liberal ideals, understood the dangers of religious extremism and theocratic rule. They enshrined the separation of church and state in the Constitution, and, for the first time in history, equal liberty of conscience for all was protected by law.

Although the Founders held diverse religious beliefs, they would have recognized Jesus’ teachings from the Sermon on the Mount. They emphasized the importance of liberty of conscience, a principle closely aligned with their vision for a nation where freedom of religion meant equal freedom for all to worship — or not worship — freely while being protected from religious imposition.

Yet, in today’s political climate, we see a resurgence of the Jesus of Revelation, invoked by those who seek to blur the lines between church and state to impose a particular religious vision on the entire nation. This is not just a theological debate; it’s a struggle for the country’s soul.

The choice between these two Jesuses is not merely a matter of faith but a question of governance. At a time when Christian Nationalism’s angry and arrogant Jesus of Revelation is pervasive and powerful, will Christians in the United States have the courage to openly embrace the Jesus who calls his followers to a higher standard of personal morality and respect for individual conscience? Or will they succumb to the temptation of a Jesus who justifies the wielding of political power in the name of religious domination?

In the end, the separation of church and state is not just about keeping religion out of government; it’s about preserving the integrity of both. The Jesus of the Sermon on the Mount knew this. The Jesus of Revelation, in the hands of theocrats, threatens church and state alike. The Founders’ greatest gift was recognizing that true faith or no faith doesn’t need the sword of government to thrive. Let’s not forget that.