Editor’s note: Two new books examine aspects of church-state relations that may be of interest to Church & State readers. Here the authors discuss their new works.

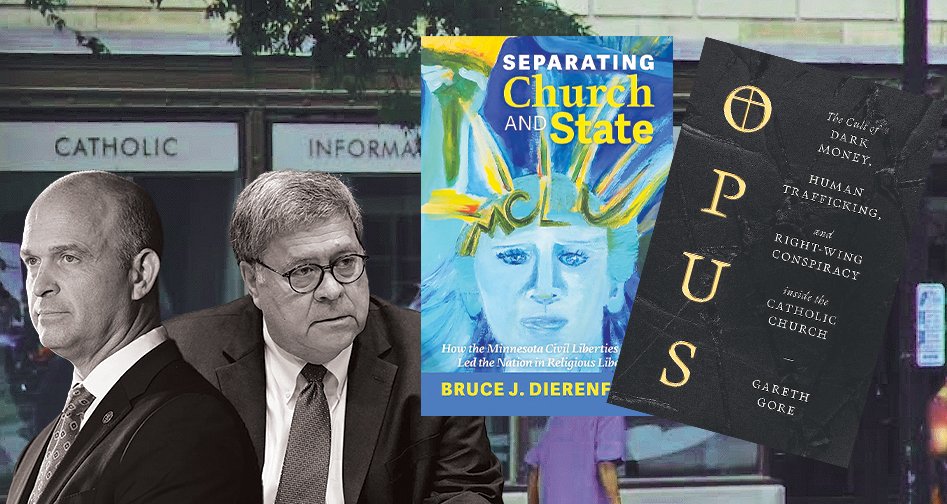

‘Holy Shamelessness’: The real agenda driving Opus Dei

By Gareth Gore

Nestled among the lobbying firms and think tanks on K Street in downtown Washington, D.C., the Catholic Information Center (CIC) looks inconspicuous and unassuming. The simple chapel and bookstore professes to be nothing more than a meeting point for ordinary Catholics looking to take time out of their busy days to attend mass, take confession or browse through its bookshelves.

But the blue plaque in the lobby tells a very different story. Boastfully proclaiming itself to be “the closest tabernacle to the White House,” the plaque betrays a fixation with proximity to power that has long defined Opus Dei, the secretive Catholic group that runs the center — and which casts a very different light on its location at the heart of the K Street lobbying industry.

To cast an eye over the names of its current and most recent board members is like flicking through a Who’s Who of the D.C. conservative political and legal elite. There’s the Supreme Court shaper Leonard Leo, former Attorney General Bill Barr and former White House chief counsel Pat Cipollone. Kevin Roberts, president of the Heritage Foundation and architect of Project 2025, is a regular.

Opus Dei didn’t just find itself here by accident. For decades, it’s been pumping resources into penetrating D.C.’s conservative political and legal elite. And it’s a strategy that has reaped an impressive harvest. The late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia was a regular at its retreats, while Republican Party grandees such as Rick Santorum and Sam Brownback are linked to the group.

The organization — much like the Catholic Information Center — presents as inconspicuous and unassuming. Taking advantage of the legitimacy and special status conferred upon it by the church, Opus Dei seeks out these powerful figures and offers to help them become better Catholics — through intense prayer, study and its own unique form of “spiritual guidance.”

But this is a front that is used to reel in the rich and the powerful — and give Opus Dei influence over public policy and public institutions. Thanks to hundreds of pages of internal documents that were secreted out of the organization by former members, and which are republished extensively in my new book Opus, we now have a deeper understanding of the group’s methods and aims.

Opus Dei was formed in 1928 by the Spanish priest Josemaría Escrivá, who went around telling everyone that he had received a vision from God for a new organization that would help ordinary Catholics to live out their faith more seriously — without needing to become priests or nuns — by striving for perfection in everything they did. Who could possibly object to that?

The organization has carefully upheld this narrative ever since. But we now know that, in the years immediately after its founding, Escrivá began to fundamentally revise this “vision.” Horrified by what he saw around him — workers demanding rights and turning their backs on the church — he began to remold the organization into something altogether more political, reactionary — and militant.

For Escrivá, the Opus Dei membership was a “rising militia” tasked with infiltrating the corridors of power and encouraged to take charge of cultural, social and government institutions. He saw his followers as “an intravenous injection, inserted into the circulatory torrent of society” to reverse progressive advances and shape society according to his anti-modern, ultra-traditionalist beliefs.

Opus Dei has kept its plans hidden, including from the Vatican, for almost a century. Most of its members have no clue about these secret internal documents or of the way that the organization abuses the legitimacy conferred upon it by the Vatican to lure unsuspecting individuals (including children) into its network, which it then works to achieve its reactionary agenda.

The CIC is just the tip of the iceberg. Opus Dei lurks behind a vast network of seemingly civil institutions that double up — either as recruitment initiatives or political action initiatives, or both. That network includes schools, universities, advocacy groups and hundreds of nonprofits. Faith and spirituality are mere fronts for what at its very core is a deeply political organization.

But faith also justifies whatever is necessary. Opus Dei has actively encouraged its membership to consider themselves above the law in their mission to “re-Christianize” the world — what Escrivá euphemistically termed “holy intransigence, holy coercion and holy shamelessness.” He encouraged them to use any means at their disposal, including public funds and government resources.

Over the years, many of its members have taken this message to the extreme. There are multiple alleged instances of money laundering, defrauding the government and even the trafficking of young girls — Opus Dei was formally accused of this recently in Argentina. Faith and religion provide a convenient shield to hide behind — to avoid oversight, regulation and, in some extreme cases, even justice.

Gareth Gore is the author of Opus: The Cult of Dark Money, Human Trafficking, and Right-Wing Conspiracy Inside the Catholic Church (Simon & Schuster).

The Minnesota connection: How a state ACLU chapter led the nation in protecting religious freedom

By Bruce J. Dierenfield

The challenge of keeping church and state separate was not settled by the adoption of the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution (which states that Congress shall make no law “respecting an establishment of religion”).

As a result, this perennial challenge has invariably been taken up by several nonprofit organizations, including those that are non-sectarian. One of these groups, of course, was Americans United. In Minnesota, after World War II, the most prominent and successful group to challenge religious activities with the imprimatur or direct support of the state government was the American Civil Liberties Union’s affiliate.

My new book, Separating Church and State: How the Minnesota Civil Liberties Union Led the Nation in Religious Liberty, is an authorized study of the MCLU’s remarkable multi-pronged commitment to defend the First Amendment. It is based on the MCLU’s archives, many first-person interviews, newspaper articles and editorials, and pertinent scholarly publications.

In the book, I show how the MCLU took on a series of infringements of the First Amendment, almost invariably committed by Christians. These infringements included religious activities in public schools, such as teacher-led prayers, reading from the King James Bible, Bible distribution by the Gideons International, church night, shared-time, Christmas pageants, prayers by clerics at graduation, baccalaureates and outright proselytism of all-too-often impressionable students by Youth for Christ and similar groups. Additionally, the state of Minnesota provided tuition reimbursement to parents sending their children to parochial — meaning “religious” — schools.

Other issues addressed in this book include preferential treatment given to religious leaders and groups when using government buildings, as well as tax breaks or privileged locations on state property for religious organizations. Even in public venues, such as prisons, the government favored certain religious groups over others. Native American religious ceremonies in prison were held at inconvenient times in a boxing ring in the basement, rather than in customary sweat lodges, which were presumed to be hiding drug use. Medicine men were suspected of smuggling illicit drugs to incarcerated Native American groups and their sacramental tobacco and peyote were trashed. Members of Hare Krishna were hindered, when not prohibited, from seeking converts in the public square.

One of the most disturbing actions taken to coerce someone’s religious belief involved “deprogramming.” Some Christian or Jewish parents hired deprogrammers to kidnap their adult children, hold them against their will and pressure them to abandon their affiliation with religious minorities — dubbed “cults” — such as the Unification Church of the Rev. Sun Myung Moon of South Korea. In a reprehensible abdication of their responsibility, county attorneys largely refused to intercede in such matters, claiming that no jury would convict the parents involved.

For two generations after World War II, the MCLU employed a variety of means to circumscribe unconstitutional religious activity in the public sphere. For example, the MCLU’s indefatigable executive director operated like an “army general” hellbent on preserving the line between church and state. He complained to public school superintendents when illegal religious activity occurred, gave pep talks to teacher unions, held attention-grabbing news conferences, recruited pro bono attorneys, served as a plaintiff in high-profile court cases and served on innumerable governor commissions to spread the “gospel” of church-state separation. So forceful, sometimes intimidating, was this executive director that the mere mention of the phrase “Minnesota Civil Liberties Union” sent a shudder down the collective spines of government officials whose actions illegally countenanced, if not promoted, abridgments of church-state separation.

There were, admittedly, other forces at work besides the MCLU’s crusade against illegal interaction between church and state. These larger developments included an increasingly diverse population, especially immigrants from less familiar places; increasing urbanization, which brought more religious groups into contact with one another; and increasing secularization in society as a whole, especially among mainline Christianity and non-Orthodox Judaism. But it was the MCLU that took advantage of these trends and was the indispensable player in the ongoing battle to keep church and state separate.

Bruce J. Dierenfield is professor emeritus of recent American history at Canisius College in Buffalo.