Editor’s note: Katherine Stewart is an investigative journalist whose work focuses on the threat of Christian Nationalism. She is the author of The Power Worshippers: Inside the Dangerous Rise of Religious Nationalism and The Good News Club: The Christian Right’s Stealth Assault on America’s Children. She’s also a member of Americans United’s Board of Trustees.

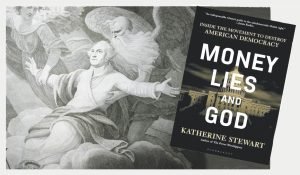

Stewart’s latest book, Money, Lies, and God: Inside the Movement to Destroy American Democracy (Bloomsbury Publishing), will be released next month. In this Q&A with Church & State Staff Writer Rob Boston, Stewart provides a sneak peek at the book’s central themes.

Boston: What is the premise of your book, and why did you choose the title Money, Lies, and God?

Stewart: My new book is about the anti-democratic political movement in the U.S. As I show, this movement draws on a range of different actors, many of whom have mutually incompatible goals. I title the book Money, Lies, and God because, first, money is a huge part of the story, meaning that huge concentrations of wealth have destabilized the political system. Second, lies, or conscious disinformation, is another huge feature of this movement. And number three, God, because the most important ideological framework for the largest part of this movement is Christian Nationalism. The conclusion I draw from over 15 years of reporting on the subject is that this movement is intrinsically destructive or nihilistic. But it can be defeated if we address fundamental structural problems in the American political economy.

Boston: The assault on the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, should have been a shock to our political system. Instead, Donald Trump, the man who fomented it, has won a second term. He might even pardon some of the insurrectionists. Americans watched the center of their democracy under siege — and many don’t seem to care. Why didn’t this event mark a turning point and usher in a new era of support for American democracy?

Stewart: The January 6 assault on the U.S. Capitol failed to usher in a new era of commitment to democracy because the movement that is the focus of my concern, the movement that is now in power, is not only fundamentally antidemocratic but extremely powerful; it has been built up over decades of investment in its infrastructure. Many of its supporters simply don’t recognize that American democracy might be destroyed; others simply don’t care. It is more important for them to put a strongman in power who can advance what they believe are the “correct” policies against what they believe is a dangerous radical left.

How did they come to this conclusion? Part of the reason is that they have been colossally misinformed, and that is how they rationalize their choices at the ballot box. Authoritarianism loves a misinformed and disinformed public, and the anti-democratic movement has funded massive propaganda campaigns that have led us to where we are today. A longer explanation as to why we are where we are today involves the effectiveness of the anti-democratic movement’s voter turnout operations, and in the book I delve into each of these features and more.

Boston: Your book talks about “five main categories in the anti-democratic movement” — the funders, the thinkers, the sergeants, the power players and the foot soldiers. In which camp or camps do we find most Christian Nationalists? What is their role?

Stewart: Christian Nationalism is not just an ideology. It is also a dysfunction or dynamic that afflicts political systems. It involves or makes use of certain views on history, national identity, and on the issues, but it draws support from others who may not necessarily subscribe to those views. So, while some of the funders, who are absolutely essential to this dynamic, seek to promote those views, others aren’t particularly serious about their Christianity, and some key funders are not Christian at all.

If you’re looking for the people who articulate Christian Nationalism in its most extreme theocratic form, you’ll find most of them among the sergeants and the power players, and among a sector of the foot soldiers. It is likely that most of the rank and file is willing to sign up for vague propositions coming from this extremist ideology, but quite a few would be surprised to discover what is actually being done in their name.

Boston: Promotional material for the book states, “Christian nationalism and the New Right are the power couple of American authoritarianism.” Can you say more about this?

Stewart: Christian Nationalism is useful in motivating large groups of voters. It is not always the right tool for wielding power. And the anti-democratic movement can also draw on a lot of energy that doesn’t come straight from religious organizations. I am thinking in particular of the “men’s rights” movement, along with some of the nativist and pro-natalism movements. These groups tend to align with Christian Nationalism in their goals, but they often arise from different groups in society. The New Right answers to these needs. It is where you’ll find the whisperers, or thinkers, who tell the political leaders of the anti-democratic movement how to wield power. The New Right also appeals to these other constituencies for anti-democratic politics. It is important to add that the New Right draws on a range of sources that would probably make most people who identify as Christian somewhat uncomfortable. Many of its leaders draw directly on pro-Nazi and other fascist theorists from the 20th century.

Boston: Public education serves 90% of America’s children. Yet these schools have been flashpoints for the culture wars for decades, and that seems likely to only increase. What does the New Right/Christian Nationalist coalition have in store for our public schools?

Stewart: The fundamental goal is to create a national network of publicly financed religious schools that explicitly favor conservative forms of Christianity. Superficially, it looks like they are trying to achieve this aim by forcing their initiatives and programming into the public schools. That’s the apparent motivation of the recent law in Texas that offers to pay schools to teach elementary-age children a sectarian Christian curricula, for instance, or the Louisiana and Oklahoma rules imposing the Bible in schools.

However, the ultimate goal is to undermine public education through these initiatives in order to pave the way for privatization. The division and conflict these initiatives promote in diverse public school communities is not an unintended consequence of their activity; it is precisely the point. The desired end state is a system where taxpayers supply parents with vouchers, and then parents use those vouchers to funnel money into religious and ideologically right-wing schools. Speaking rather cynically, it’s a twofer, because this promises to be very profitable for the religiously motivated entrepreneurs involved, and at the same time it is intended to help build a constituency for Christian Nationalist politics.

Boston: There is some debate whether it’s appropriate to use the “F-word” — fascism — to describe the movement you write about. What is your view? Is this movement fascistic?

Stewart: It is perfectly appropriate. Yes, we need to understand that what we face today, in the American context, is distinct from earlier 20th century forms of fascism, but those also differed among themselves. The main elements of fascism are all in place in this movement, and if we are too frightened to call them out, we will never be able to defeat them.

One core idea of fascism is the idea that the nation must be defended from an enemy within, which is characterized as “other”: sub-human, pernicious, even demonic. Democracy starts with “We the People”; fascism starts with “we the righteous; they the vermin.”

Number two: Fascism historically involves a fusion between the ruling party and a significant slice of the economic elites in a circle of graft and cronyism. This is likely to be very much in evidence in the next four years of the second Trump administration.

And third, fascism embraces the absolute need for strongman rule, above and beyond the rule of law, against what is taken to be an existential threat to the nation.

There are additional features that the movement I describe shares with other iterations of fascism. Where appropriate, we shouldn’t be afraid to call it by its name.

Boston: Your book concludes with a chapter titled, “The Way Forward?” In the wake of the election, some people are wondering if there is a way forward. Do we have any cause for optimism? If so, what’s the plan?

Stewart: One thing we have going for us is that fascists are often incompetent. Over the course of history, many have ended up destroying themselves. So, the question, in a way, is how much of our democracy can they damage and destroy before they take themselves down? On that score, there is some grim hope.

In addition, we can take some grim hope from the fact that it is hard to get things done in an immense and complicated machine like the U.S. government. Some of the most destructive policies that the Trump administration is proposing, including internment camps, the use of military against perceived enemies within the United States and massive deportations, are going to be very difficult and very expensive to implement. Many of the measures they are proposing will be snarled up in court, and one hopes that there will be sufficient recognition of the need for effective political mobilization that will shift the balance of power over the next two to four years.

Those who value our democracy and its institutions may be upset about the election results, but they shouldn’t despair. In the 2024 election, Trump failed to win more than a very slim majority of the popular vote, and we know there’s a significant slice of non-ideological voters that swing with their perceptions of so-called pocketbook issues. While a large sector of the Trump base is locked in, another sector is not. So, another grim source of hope may come from the fact that this slice of the electorate will not see their grievances, in particular their economic grievances, addressed by a government that will be run for the benefit of wealthy cronies at the expense of the workforce. They may be open to voting differently in elections to come.

We must remember that we have a lot of institutions that matter, including the judiciary, law enforcement, educational institutions, a reasonably robust private sector and economy and local and state governments. These institutions are now going to go through a stress test: Will they hold up against the corrosive power of authoritarianism? Because what authoritarians ultimately want is to dissolve any systems or structures that stand in the way of their power.

Boston: Is there anything else you would like to add?

Stewart: There is clearly work to be done in the area of voter turnout. Right now, the right-wing machine, especially with its support from right-wing religious institutions and extensive propaganda networks, has a clear advantage, both organizationally and financially. But there’s a lot that democracy-supporters can do, and need to do, to bring out pro-democracy voters. We may not wish to emulate their disingenuity, but we would do well to learn from their tactics.