trial of teacher John T. Scopes took place (Photo by Hulton Archive)

One hundred years ago, Dayton, Tenn., was a sleepy little town of about 2,000 souls with an image problem.

Like a lot of small communities all over the country, Dayton didn’t have much going on, even in the middle of the “Roaring Twenties.” A local resident, George W. Rappleyea, thought that should change — and he soon formulated a plan of action that hinged on a controversial new state law.

In March of 1925, the Tennessee legislature had passed the Butler Act, a measure that made it illegal to teach in the state’s public schools the theory of human evolution.

Under the Butler Act, which was named for its sponsor, state Rep. John W. Butler, it was “unlawful for any teacher in any of the Universities, Normals and all other public schools of the State which are supported in whole or in part by the public school funds of the State, to teach any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals.” Tennessee’s Democratic governor, Austin Peay, signed it into law March 21, 1925.

Violations of the law were considered a misdemeanor and could result in a fine between $100 and $500 for each offense ($1,800-$9,100 in today’s money.)

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) had made it clear that it was eager to challenge the law. But to do that, it would need a defendant — a teacher who was willing to openly break the law and face the consequences.

That’s where Rappleyea came in. He knew about the ACLU’s interest in challenging the Butler Act and argued to Dayton’s leaders that a trial in their community would put Dayton on the map.

Enter science teacher John T. Scopes.

If, like most Americans, what you know about this trial comes from the play (and later film) “Inherit the Wind,” then you may have an image in your head of Scopes being confronted in class by local officials as soon as he starts teaching evolution and hauled off to jail.

That’s a dramatic scene from the 1960 film, but there’s one problem: It never happened. In fact, Scopes wasn’t even sure if he had taught evolution, but he agreed that he had taught from a science textbook that included the concept. He was charged but never spent any time behind bars.

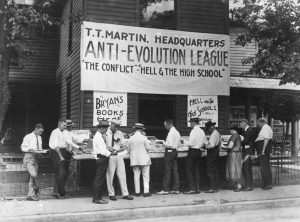

The trial in The State of Tennessee v. John Thomas Scopes turned out to be the public relations bonanza Rappleyea and the town fathers hoped for. It was a media circus. As History.com notes, “Outside, Dayton took on a carnival-like atmosphere as an exhibit featuring two chimpanzees and a supposed ‘missing link’ opened in town, and vendors sold Bibles, toy monkeys, hot dogs, and lemonade.”

The trial in The State of Tennessee v. John Thomas Scopes turned out to be the public relations bonanza Rappleyea and the town fathers hoped for. It was a media circus. As History.com notes, “Outside, Dayton took on a carnival-like atmosphere as an exhibit featuring two chimpanzees and a supposed ‘missing link’ opened in town, and vendors sold Bibles, toy monkeys, hot dogs, and lemonade.”

Inside the courthouse, two legal titans duked it out: Clarence Darrow defended Scopes, and William Jennings Bryan represented the state. Both men were among the most famous public figures in America at the time. Darrow was fresh from gaining national headlines during the 1924 extended sentencing hearing of Illinois “thrill killers” Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb, where he managed to secure lengthy prison terms for the two instead of the death penalty. Bryan was well known to Americans for being a powerful populist orator who was the Democratic Party’s nominee for president in 1896, 1900 and 1908.

But despite the buildup, the actual trial turned out to be something of a bust. Judge John Raulston essentially gutted Darrow’s case when he refused to allow expert testimony, limiting the trial to the narrow question of whether Scopes had violated the law. Since Scopes agreed he had taught from a text that contained evolution (although it was never clear that he had taught the concept in a manner that denied “the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible”), the verdict was never really in doubt.

Nevertheless, the trial is remembered for some unusual moments. Some sessions were held outside due to the oppressive heat in the courtroom, and in one unconventional twist, Bryan ended up on the stand being quizzed by Darrow about his fundamentalist religious beliefs.

On July 21, 1925, a jury found Scopes guilty, and he was fined $100. Although the Tennessee Supreme Court later overturned his conviction on a technicality, it also upheld the Butler Act.

Yet a century later, this legal battle continues to resonate. Why?

“There’s no question that the Scopes trial was artificial, overblown — thanks to the titanic figures of Darrow, Bryan and the reporter H. L. Mencken — and inconclusive,” Glenn Branch, deputy director of the National Center for Science Education (NCSE), told Church & State. “So, it’s a fair question: Why do we bother to remember this controversy of the 1920s, but have forgotten plenty of others that roiled the nation at the same time? The answer is that the Scopes trial highlighted broader themes that continue to resonate today, such as the importance of church-state separation, the complex relationships between science and religion and the potentiality for conflict between democracy and expertise.”

Many people believe the real impact of the trial is that it discredited attempts by fundamentalists to block the teaching of evolution. That’s not quite accurate either, Branch says.

Branch notes that after the trial Arkansas and Mississippi joined Tennessee in enacting bills similar to the Butler Act. He adds, “Fearful of controversy, publishers began to downplay evolution in their textbooks, sometimes using euphemisms for evolution or omitting the e-word from the index. True, fundamentalist interest in pursuing the antievolution crusade subsided after the 1920s, but that was probably due as much to the Depression as anything. While there isn’t a pre-Scopes-trial survey to provide a baseline, a 1939–1940 survey discouragingly suggested that only slightly more than half of high school biology teachers presented evolution as a central principle of biology.”

Americans began to pay more attention to the state of science education after an incident that came decades after the Scopes trial: On Oct. 4, 1957, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, the world’s first artificial satellite. Rattled by the Soviet achievement, members of Congress began pushing for a bill that would, for the first time, provide federal funding for higher education. The resulting legislation, the National Defense Education Act of 1958, emphasized education in science, math and foreign languages.

The changes filtered down to the secondary school level. Around the same time, the National Science Foundation (NSF) began overhauling science and math curricula and emphasizing teacher training.

Using an NSF grant, the Biological Sciences Curriculum Study (BSCS), an education center, was formed in 1958. BSCS (now known as BSCS Science Learning), focused on improving how high school biology was taught. The group published three textbooks, all of which emphasized evolution.

But in parts of the country where anti-evolution laws remained on the books, some public school teachers remained a bit wary. Arkansas’ anti-evolution law had been in place since 1928, and while it wasn’t really being enforced, its presence intimidated some science teachers. The law, which made it illegal for any public schools “to teach the theory or doctrine that mankind ascended or descended from a lower order of animals” or to “adopt or use in any such institution a textbook that teaches the doctrine or theory that mankind descended or ascended from a lower order of animals,” imposed fines of $500. That was steep price to pay in 1965, when the average public school teacher in Arkansas made less than $2,000 a year.

In 1965, officials at a high school in Little Rock adopted a new biology book that stressed evolutionary theory. Susan Epperson, who taught 10th grade biology, was approached by advocates who wanted to get the law off the books. She agreed to serve as the plaintiff in a test case.

An Arkansas state court ruled for Epperson, but the state’s high court later reversed that ruling. The case, Epperson v. Arkansas, was then appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Oral arguments were held on Oct. 16, 1968. Less than a month later, the court struck down the Arkansas statute in a 9-0 ruling authored by Justice Abe Fortas.

“There is and can be no doubt that the First Amendment does not permit the State to require that teaching and learning must be tailored to the principles or prohibitions of any religious sect or dogma,” Fortas wrote. “[N]o suggestion has been made that Arkansas’ law may be justified by considerations of state policy other than the religious views of some of its citizens. It is clear that fundamentalist sectarian conviction was and is the law’s reason for existence.”

The defeat stung fundamentalist opponents of evolution, but they didn’t give up. The rise of the Moral Majority and similar Religious Right groups in the late 1970s forged a new political power structure for religious extremists. Public schools became one of their targets.

In June 1980, Louisiana state Sen. Bill P. Keith proposed what was called a “balanced treatment” law. Keith’s measure didn’t require public schools to stop teaching evolution; instead, it stated that if a school chose to do so, it also had to offer instruction in “creation science.” The measure became law about a year later, sparking a court challenge. The case, Edwards v. Aguillard, reached the U.S. Supreme Court, which, ruling 7-2 in 1987, invalidated the Louisiana law.

Lower federal courts also upheld the teaching of evolution against religiously based attacks. In 2005, a federal judge in Pennsylvania struck down the teaching of “intelligent design” creationism (ID) in Dover public schools. The case, brought by Americans United, the ACLU, the NCSE and the law firm Pepper Hamilton, resulted in a powerful 139-page opinion by U.S. District Judge John E. Jones III.

In Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District, Jones held that by approving a pro-ID policy, the Dover School Board “consciously chose to change Dover’s biology curriculum to advance Religion.” He added that the court had seen a “wealth of evidence which reveals that the District’s purpose was to advance creationism, an inherently religious view….”

Voters in this rural community were disgusted with what the board had done and ousted the pro-ID slate in the next election. The new board reinstated evolution, and there was no appeal of Jones’ ruling.

So where are we now? Unfortunately, in recent years, the legal landscape has shifted considerably, especially at the U.S. Supreme Court where legal precedents that have protected the secular nature of public schools are being steadily eroded. For example, in the 1971 decision Lemon v. Kurtzman, the Supreme Court fashioned a three-part test for determining church-state violations. The first prong stated that laws must have a valid secular purpose. Unfortunately, the current ultraconservative majority on the high court a few years ago rejected the Lemon Test.

“This anniversary has particular significance for a number of reasons,” said Alexander Gouzoules, an associate professor of law at the University of Missouri School of Law and co-author of the new book The Hundred Years’ Trial: Law, Evolution, and the Long Shadow of Scopes v. Tennessee. “The vast majority of cases involving evolution that have been decided since the 1970s were decided through application of the Lemon Test, which has now been overruled. That doesn’t necessarily mean that evolution will vanish from public education, but it does make this issue more legally unsettled than it has been at any time in recent memory.”

Added Gouzoules, “Scopes also provides important and timely lessons about public education. Evolution is one area where educators have been unable — for over a century since Scopes — to fully communicate to the public the nature of scientific consensus among experts. Today, we see similar problems with respect to climate change and vaccine effectiveness. A century of indecisive conflict over evolution should serve as a dire warning about the challenges of effective public education in those areas as well.”

Gouzoules, who served as a litigation fellow at Americans United from 2019 to 2021, wrote the book with his father, Harold Gouzoules, an evolutionary biologist.

“Writing from today’s vantage point, we also find that the legacy of Scopes appears quite different than it did in early periods, when many of the major works covering the trial were published,” Alexander Gouzoules told Church & State. “In an era of ongoing revisions to once-settled constitutional law, and an increasing tendency of political actors to challenge well established scientific conclusions, it is high time to reexamine many of the questions raised by the Scopes trial that once appeared to have been answered.”

NCSE’s Branch said there’s cause for optimism and concern.

“On the one hand, evolution education is increasing and improving overall, and the chance that a local teacher is espousing creationism in the classroom is dwindling,” Branch said. “Even so, teachers still need moral and material support from their community to be able to teach evolution accurately, honestly, and confidently, and creationist encroachments on the classroom still need to be resisted.

“NCSE and AU continue to assist people facing attacks on evolution education in their communities,” Branch continued. “On the other hand, in light of the upheaval in church-state jurisprudence, it is entirely possible that the foes of evolution education will redouble their efforts in the hopes of making up lost ground. Now more than ever, eternal vigilance on the part of the friends of evolution education is in order.”

And what about Dayton, the small town that wanted to make a big splash? The legacy of the Scopes trial lives on there and in surrounding Rhea County. Town officials have embraced the trial, perhaps aware that it provides an important economic boost to a community whose population remains just over 7,000.

In the late 1980s, Dayton began hosting an annual Scopes Trial Festival, and the Rhea County Heritage and Scopes Trial Museum offers a deep dive into the events of summer of 1925. The town has been hosting a series of events this year to mark the centennial. (See www.scopes100.com for more information.)

As for the principals in the case, their paths led them away from Dayton. Scopes quickly grew weary of the notoriety he gained from the trial. In the fall of 1925, he began studies at the University of Chicago where he earned a graduate degree in geology. But no school in Tennessee would hire him after he graduated, so Scopes and his wife moved to his native Kentucky. He ran unsuccessfully for the U.S. House of Representatives on the Socialist ticket in 1932 and then took a job in the oil industry. Scopes died of cancer in 1970 in Shreveport, La. He was 70 years old.

Darrow worked another high-profile case after the trial, successfully defending Ossian Sweet, a Black physician in Detroit who was charged with murder after defending his home from a mob of white rioters who were trying to drive his family out of the neighborhood. Darrow died of heart disease in 1938.

Bryan, whose performance during the trial had been widely panned, died just five days after it ended. The cause was apoplexy.

Both Bryan and Darrow have a presence in Dayton, however. In 2005, the town accepted a large statue of Bryan from nearby Bryan College and placed it outside the Rhea County courthouse. Twelve years later, the Freedom From Religion Foundation and other groups raised funds for a statue of Darrow to be erected nearby. (Americans United endorsed the move, and a statement from the group was included in the program created for the statue’s unveiling.)

It’s pretty clear that 100 years later, the issues raised in a Tennessee courtroom during a steamy summer in Dayton still have the power to provoke strong reactions.

“Trial of the century” has become something of a cliché, and it seems one comes along every few years. One scholar who has studied the case argues that only the Scopes trial deserves that label.

“Dozens of prosecutions have received such a designation over the years,” observed Edward J. Larson in his 1997 book Summer For The Gods: The Scopes Trial and America’s Continuing Debate Over Science and Religion, “but only the Scopes trial fully lives up its billing by continuing to echo through the century.”