As a strong supporter of Americans United’s defense of church-state separation, as well as the Constitution’s clearly established principle of “no establishment” (of any religion or religion itself), I’m also sensitive to the fact that the phrase “separation of church and state” does not appear in the First Amendment. In my view, a consistent response to Christian Nationalists who are quick to point that out, ought to be: “That’s correct, the phrase is not there, yet, no religion can be set as the standard in our secular society.”

In practice, this means there must be a hedge, if not a wall — or flashing warning signs with alarms — to maintain some respectful distance. Let’s establish the ground rules: the concept of separation between religion and government never means a person of faith can’t serve in political office. On the other hand, to separate private piety from public service doesn’t mean the laws of the land don’t apply equally to religious entities. As Thomas Jefferson reasoned, freedom of conscience — free inquiry — is protected; the attempt to force one’s conscience on others is not protected. Perhaps nowhere is this tension most prominent right now than in the crusade to “get the Bible back” into public schools.

The truth is, the Bible has always been in public schools — in pockets, packs or prayers. However, should it be taught? Not if the Bible is taught as an alternative to science or history (and definitely not as a science and history textbook — there is no “spiritual science” just as there is no “holy history”). Not if the Bible is taught as “God’s Word” instead of literature written by human beings, one ancient writing among many. Not if the Bible is taught as an exclusively Christian book, ignoring the fact it contains Jewish writings. And certainly not if the Bible is presented as a kind of weapon or tool for morality police to indoctrinate young minds in one narrow theology. So, can the Bible be taught as one element of a larger secular educational program? I think it can. In fact, I think it must.

A high school classmate posted the news that one of our beloved teachers had died. Mr. Hansen was an English teacher with long hair and a beard (this was the 1970s after all). I took several classes from “Dave” (he encouraged the familiarity), including a class on poetry, and still have two of the poetry collections we read, tattered and worn by the years.

The other class I took from Dave might surprise some readers: “Bible as Literature.” Yes, in a public school. Though many seem to believe the Bible (along with prayer, and God!) was “thrown out” by the Supreme Court in the 1960s, that’s never been true. We carried our Bibles to school, prayed (silently) whenever we wanted, “shared the Gospel” without disrupting classes and generally “lived our faith” throughout the school day. As long as it didn’t distract from the purpose of public education, teachers were fine with that. As respectful professionals, cognizant of Supreme Court decisions honoring the separation of religion and state, they didn’t push their faith — if they had one — on students. I think it’s worth a trip back to high school to learn a lesson or two.

Mr. Hansen graduated from the same evangelical Christian college where I would later receive a religion and philosophy degree. I thought his elective class might give me a chance to study “my Bible” on a deeper level. I was correct, but not for the reasons I imagined. Mr. Hansen was a good teacher, and maybe a good Christian, but he was no evangelist. Sitting on his desk, as usual, he gave us an assignment to write our own version of the Genesis creation story. I was troubled. I told him it was God’s word and there was no way I would change it. Dave listened respectfully to my concerns and suggested I write my own thoughts on the two stories of creation presented in Genesis.

My fragile faith was satisfied with that, and the rest of the class held my interest, as we approached some of the more dramatic stories and read the poetic passages aloud. There was no pressure to “believe” what we were reading and discussing, only encouragement to consider the literary value of the Bible.

This personal experience aside, a serious question remains: Should the Bible be taught in public school at all? Who can teach it, and what’s the intent? I share a deep concern about this, but I think my experience in high school, as well as college and seminary, offers a potential pathway to a wise educational opportunity. Firm supporters of separation might even lead the way forward on this “radical” approach to religious literature as well as religious literacy.

A capable teacher could begin this elective course by simply having students read selected passages, discuss them and respectfully share different viewpoints. Encourage them to ask honest questions and refer to the fact there are many interpretations. Present the literary aspects of the book — after all, no matter what anyone believes, it’s a book — highlighting the historical (or claimed to be historical) narratives, as well as the legal, poetic, wisdom and legendary aspects, woven into the obvious religious elements. Constant reminders would be necessary, that people are free to believe the literature, or not, according to their “sincerely held beliefs.”

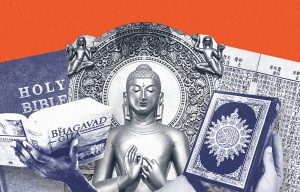

Yet, here’s the part I would add: the Bible is one among many sacred texts around the world. Therefore, what I suggest, is not an exclusive “Bible as Literature” course. What is needed the most, in my view, is a broader, more balanced, religious literacy lesson plan, that can begin — if handled thoughtfully and competently — with some reading of various scriptures representing the diversity of religious history.

Adapting educational models from adult religious education is tricky but possible. When I taught courses on “An Introduction to World Religions” and “Sacred Scriptures of the World” in congregations, the centerpiece of our study was the writings themselves, the original voices underpinning the belief systems. We became more familiar with non-biblical texts such as the Gita, the Quran, the Tao, the Analects, the Dhammapada and other sacred sources that continue to guide the lives of billions.

Facing our often fearful ignorance together, we learned that a positive and open approach to the study of religion was no threat to our faith but enhanced our knowledge and expanded empathy toward neighbors near and far. The intention was not a competition between the beliefs, or even comparison of faith traditions, but the exciting opportunity to imagine ways of cooperation and mutual learning across boundaries of belief.

In addition, I would add one other essential element to present these traditions: provide an opportunity to see and hear those who represent each community of conscience. This could add a wonderful depth to a public school class. Why not meet people in the community who practice a faith different from your family, invite them into the classroom for the students to listen to and learn from, to ask questions and become more knowledgeable about the “world of faith”? As a secular person, I would also encourage the inclusion of humanist voices in the curriculum.

No doubt, this approach to literature and literacy wouldn’t work in every school. And, let’s be honest, young people have plenty of opportunities to learn about the Bible at home, at church, in synagogue or in religious schools (plus the internet and the public library!). Why are a minority of parents clambering for “more Bible” in public schools? Aren’t they teaching enough at home? Aren’t their children getting a good education in their church?

If these parents are afraid their kids are hearing about “un-Christian” ideas and being exposed to science and critical thinking, while having to mingle with students of other faiths or no faith, maybe they ought to ask why they wish to pass along their fear-based faith to the next generation. As Americans United succinctly states: “Public schools are not Sunday schools.”

Yet, if educators wish to offer courses on the Bible in public schools, it only stands to reason — and makes common sense in a pluralistic culture — to find teachers who can present books that have inspired humanity throughout history, sources and resources that may still offer wisdom for today. It would seem quite rewarding to help students be exposed to wider viewpoints in their world. As I see it, finding and training those capable, competent, thoughtful and balanced instructors remains the greatest challenge.

Chris Highland is a teacher and writer in Asheville, N.C. Formerly a Protestant minister and interfaith chaplain, he now writes and teaches from a humanist perspective. (This article represents the personal views of the author and does not necessarily represent the views of Americans United.)