Editor’s Note: Seligman is a writer and historian. Below he introduces readers of Church & State to a little-known, but pivotal event in the long story of church-state separation violations in public schools. Seligman’s new book — The Great Christmas Boycott of 1906: Antisemitism and the Battle Over Christianity in the Public Schools (Potomac Books, 2025) — was recently released.

Today’s battle over Christianity in America’s public schools has deep roots. In the 19th century, it generally took the form of an intramural struggle between Protestants and later-arriving Catholics. But at Christmastime in 1905, when Frank Harding, the Presbyterian principal of a Brooklyn elementary school, urged his Jewish students to be more like Jesus Christ, Jews entered the fray in a big way. Harding’s exhortation was just the trigger orthodox Jewish activist Albert Lucas had been waiting for. Fresh from battling Christian settlement houses brazen about their intent to convert Jewish children, Lucas accused public schools of illegal proselytizing and the Jewish community circulated a petition calling for the principal’s ouster.

After the New York Board of Education let Harding off with a slap on the wrist, Lucas and a delegation of rabbis from all branches of Judaism testified before a committee of the board and pressed for clear guidelines about what religious practices were, and were not, permitted in the schools. Reading from the King James Bible, reciting the Lord’s Prayer, singing about the birth of a savior, posting pictures of the Madonna and staging Christmas pageants seemed to them demonstrably in conflict with the New York State Constitution, the New York City Charter and the board’s own regulations.

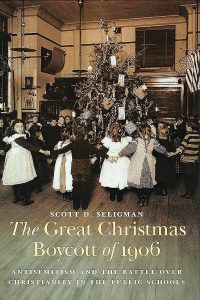

When the board ducked the issue and failed to provide answers, the Jewish community, seeking to avoid a repeat of the Harding incident, raised the stakes. Responding to an urgent plea in the Yiddish press for a boycott, Jewish parents across the city kept their children home on the day of the 1906 school Christmas pageants.

“When Jews demand that there be no place for religion in the public schools, they are not asking for favors,” the Yidishes Tageblatt (Jewish Daily News) declared. “They are demanding something already recognized by the founders of our land that is also found in the state constitution. The officials want to wriggle out of their clear duty, and we mustn’t allow them to do that. Empty seats in the Jewish neighborhoods will speak more loudly than all the protests,” the paper added.

And they did. As many as 75% of the students in Jewish neighborhoods stayed home that day, and the Board of Education got the message. Feeling the pressure, board members finally moved to exclude sectarian hymns and religious compositions.

But the ban, once announced, generated an enormous antisemitic backlash. In letters to the editor and opinion pieces, writers decried a Hebrew attack on Christmas, a Jewish conspiracy to deprive Christian children of their legitimate rights and an attempt to secularize — or, according to some, to Judaize — the whole country. Jews were accused of being something less than true Americans. They were advised to be grateful for the “asylum” granted them in America out of the goodness of Christian hearts and not to make waves. And they were told that if anti-Jewish sentiment increased as a result of the protest, they would have only themselves to blame. None of the critics gave serious consideration to the basic question of principle being raised by Lucas and company: whether public schools were an appropriate or legal venue for Christmas celebrations. Where Lucas and company wished to fight a battle over the law, their detractors relied on condescension, patriotism, antisemitism, tradition and outright falsehood. But the backlash was more than enough to persuade the conflict-averse board to rescind most of its order.

Religion has never been absent from American public schools, and the Harding case raised the perennial issue of how much of it — if any —should be permitted. The Great Christmas Boycott of 1906 traces the school Christmas celebration dispute to the present day. Since politics appear unlikely ever to permit an unalloyed victory, still less a long-lasting one, Jewish organizations in the 21st century have moved on to fighting Christian Nationalism in other ways they believe are more winnable.