In the late 19th century, America’s public libraries, in conformity with white Christian norms, largely remained the domain of white males. Though the First Amendment had long ago separated church and state, familial biblical patriarchy widely restricted religious freedoms. If women were to obtain the same rights as men, an 1871 diatribe in The Southern Magazine warned, “it will destroy Christianity and civilization in America.”

Those “patriarchal gender norms remained firmly entrenched” in the early 20th century, notes Steven Ruggles — Regents Professor of History and Population Studies at the University of Minnesota — in “Patriarchy, Power, and Pay: The Transformation of American Families, 1800–2015.” By law, wives had little autonomy, “and patriarchal authority was still enforced through violence.”

Nonetheless, by the 1920s, nearly 90% of librarians were women, according to a study of census records. This remarkable transformation came about because men reframed librarians’ work as feminine — work outside of the home that did not threaten biblical patriarchy’s gender norms.

Those familial norms largely remained when, following World War II, politically driven, anti-communist fears pressed upon America’s libraries. Facing anger from white Christians critical of libraries carrying books and other materials sympathetic with, or favorable toward, the Soviet Union, librarians found themselves on the defensive.

Responding, the American Library Association (ALA) in 1948 updated its Library Bill of Rights. Libraries were not to exclude books due to “the political or religious views of the writer.” Rather, library materials should strive to present “all points of view,” instead of succumbing to “partisan or doctrinal disapproval.”

It was not an easy task. Further stoking public anger, politically minded evangelist Billy Graham — fervent supporter of U.S. Senator Joseph McCarthy (R-Wisc.), leading figure in a witch hunt to oust alleged American communists — preached to millions, declaring communism to be “Satan’s religion.” Entangling politics and religion, Graham’s anti-communism evangelical crusades blessed McCarthy’s ruthless quest. Graham’s influence also contributed to the rise of a parallel, nationalist civil religion, a precursor to modern Christian Nationalism.

During those fraught years of government opposition to “godless” communism, politicized religious pressure led to the words “Under God” being added to the Pledge of Allegiance. In addition, the phrase “In God We Trust” was added to paper currency and declared by Congress to be the nation’s motto. Caught in the crossfire of politics and religion, public librarians during the “Red Scare” struggled with calls for suppressing “un-American” beliefs and the accompanying spectacle of public book burnings. Some felt forced to self-censor books. Others lost their jobs.

But empowered by their Library Bill of Rights, many librarians courageously fought back against ever-rising censorship and increasing harms. Soon their resistance led to an ALA “Freedom to Read” declaration, which in November 1953 received a strong endorsement from President Dwight Eisenhower.

Praising librarians who “serve the precious liberties of our nation: freedom of inquiry, freedom of the spoken and written word, freedom of exchange of ideas,” Eisenhower indirectly signaled his opposition to McCarthyism. His pressure campaign against McCarthy grew all the more thereafter, culminating with the Senate’s censure of McCarthy in December 1954.

“The era of McCarthyism was over. Ike had helped bring it to a bitter end,” wrote one Eisenhower historian.

As had librarians.

In early 1955, William S. Dix, chairman of the ALA’s Committee on Intellectual Freedom, declared that “in nearly every” local effort to censor library books, “the Library Bill of Rights or the Freedom to Read statement have been used effectively by local groups in mobilizing public opinion” for the freedom of Americans to read library books of their choice.

Or, more to the point, certain Americans.

In his hometown of Greenville, S.C., during Christmas break in his freshman year in college, a young Jesse Jackson — future Baptist minister and civil rights leader — went in search of a book for a research project. The year was 1959; racial segregation and white Christian supremacy still the norm. Not surprisingly, the city’s small, dilapidated and underfunded Black library did not have a copy of the particular volume.

Bearing a note from the Black librarian, Jackson dropped by Greenville’s white library. The white librarian was uncooperative; a policeman instructed Jackson to leave. He did. For the moment.

In the following months, Jackson and other local Black young people in Greenville persisted in their efforts to integrate the city’s white library. Being ushered out of the library failed to dampen their determination. Nor did arrests for “disorderly conduct.” Nor did mounting white Christian anger at their demands for equal rights and freedoms.

Instead, they and other civil rights protesters throughout the segregated South persisted in advancing a holistic vision of religious freedom centered on human equality and dignity.

In the summer of 1960, efforts to integrate the public library — alongside sit-ins at local department stores — led to the beginnings of integration in Greenville. Three years later, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled it was unconstitutional for the city to allow segregation in public places. Afterward, the 1964 Civil Rights Act outlawed discrimination in all public accommodations, including libraries.

The freedom movements of the 1960s also led to a nationwide “outpouring of feminist publishing and organizing,” according to Sarah M. Pritchard, retired dean of libraries and Charles Deering McCormick University Librarian at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. Perhaps “the signal event within the ALA was the founding of the Task Force on Women in 1970.”

Renamed the Feminist Task Force in 1976, the working group “focused on such issues as professional status and employment equity, pay equity legislation, women administrators, services for women library users, racism and sexism in subject headings, collection development for the growing field of women’s studies, and women in technology,” notes Pritchard, writing for the ALA’s American Librarians magazine.

More inclusive than ever, public libraries in the 1960s-70s were a front row face of an emerging, religious freedom-empowered, openly diverse America more reflective of local communities than ever before. Calls for book bans reached a low ebb.

Freedom’s advances, though, were too much for a resurgent familial biblical patriarchy rising within conservative modern white American Christianity. And once again, public libraries attracted the ire of many living within that anti-freedom, restrictive worldview.

Allying with President Ronald Reagan in the early 1980s, leading advocates of biblical patriarchy extended their reach into the White House. Emboldened, they voiced politicized rhetoric calling for spiritual warfare against perceived evil forces of “secularism” — a catchword for anything deemed ungodly.

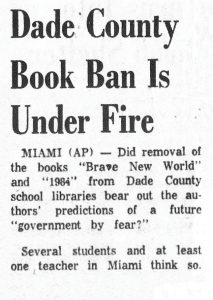

Not by coincidence, public school and municipal librarians suddenly found themselves, once again, on the defensive. Surprise turned to consternation as challenges to books rose well into the hundreds annually. As the tide grew, the ALA in 1982 debuted Banned Books Week to ensure “the availability of those unorthodox or unpopular viewpoints to all who wish to read and access them,” according to an ALA press release.

Banned Books Week was impactful: During the first two decades of this century, censorship attempts declined to around 300 titles challenged annually. But in more recent years, the number of censorship attacks has dramatically increased, driven by organized movements.

“Religious extremism, mostly in the form of Christian Nationalism, is the catalyst fueling the book banning engine currently steamrolling across school and public libraries in America,” concludes Lacie Sutherland — a former elementary teacher and currently a public librarian in Alabama — in a 2024 article titled “A Conflict Between Religious Extremism and Intellectual Freedom at Ground Zero,” published in The Political Librarian journal.

“Religious extremists, especially Christian Nationalists, have focused their attention on books written for children and young adults by or about LGBTQIA+ people or people of color,” Sutherland continues. “Christian Nationalism is comparable to an army of hate groups popping up every year with anti-diversity agendas and far-right extremists using school and library boards as their personal battlegrounds and brandishing the time-honored phrase ‘For the Children!’ as though they are the ones with children’s best interests in mind.”

Nationwide, “Pressure groups and government entities that include elected officials, board members and administrators initiated 72% of demands to censor books in school and public libraries” in 2024, according to the ALA. All of the top ten books targeted by would-be censors contained LGBTQIA+ and/or other sexual-related content. Altogether, 2,452 unique titles were targeted, “which significantly exceeds the average of 273 unique titles that were challenged annually during 2001–2020.”

The assaults on inclusive books continue. On Oct. 6, U.S. Rep. Jamie Raskin (D-Md.) introduced a resolution condemning restrictions on the freedom to read as “antidemocratic tactics used by authoritarian regimes against their people.” Two days later, the free-speech nonprofit PEN America also issued a warning: “Not since the 1950s McCarthy era of the Red Scare has censorship become so entrenched in schools.” Based on PEN America data, three-quarters of all book bans during the 2024-25 school year collectively took place in three states — Texas, Florida and Tennessee — and within schools for military families run by the U.S. Department of Defense.

Sam Olson, a cofounder of Read Freely Alabama, observes that “books are proxies for people.” Sutherland agrees: Whether in Alabama or Idaho or elsewhere, “When books about people of color and the LGBTQIA+ community are banned from libraries, it is the same as saying that those people should be banned from public spaces too.”

In 1964, Black civil rights activist leader Fannie Lou Hamer, evoking President Abraham Lincoln, put her finger on the fragility of freedom: “A house divided against itself cannot stand; America is divided against itself and without their considering us human beings, one day America will crumble.”

Censorship, inherently driven by divisive religiously rooted moralism, is an assault on equal religious freedom for all. Supporting the freedom of libraries to include books authored by, and about, diverse persons affirms constitutional church-state separation, which in turn protects the multicultural and pluralistic reality that is the United States of America.