A friend sent me a copy of a recent fundraising letter from a white Christian Nationalist organization determined to legislate the Bible into American law. We have “led the nation defending Ten Commandments displays since the early 2000s,” the organization boasts.

Their quest for a “Christian” government is in clear violation of the First Amendment’s separation of church and state. Nonetheless, the Christian Nationalist leader of the organization in question is counting on his followers’ ignorance of American history. Pleading for money, the fundraising missive proclaims that the “Ten Commandments are the basis of American law and government.” Alleged proof is in the form of 37 instances of some of the Ten Commandments being embedded within certain historic law codes. Of the 37 instances, 22 are from the 17th century and eight from the early to mid-18th century. Tellingly, the last of these citations is a quarter-century prior to the American Revolution. No citations are offered between the years 1752 and 1810.

In other words, the Christian Nationalist fundraising letter fails to identify any actual evidence of the Ten Commandments influencing “American law and government” during the nation’s founding years. No quotes are provided from the United States’ founding fathers or any legal sources during the founding era.

Bypassing the founding era in favor of the early colonial time period, the fundraising letter praises colonial “Christian” governments — Puritan, Congregationalist and Church of England/Anglican theocracies — that often incorporated biblical law, including portions of the Ten Commandments, into civil law.

Left unsaid is that those colonial “Christian” governments denied freedom of religion and conscience to others — including minority Christian groups like Baptists, Quakers and Catholics, as well as Jews, Muslims, Native Americans and non-religious people — and often harshly persecuted those who resisted.

Absent the fundraising letter, too, is the fact that Baptists — theological conservatives — especially resisted theocracy, calling for equal freedom of religion [or no religion] and conscience for all. For some 150 years, dissenters of theocracy demanded secular governance, the only form of government that would protect the freedoms of all people equally, Christians included. Many Enlightenment thinkers agreed. Together their efforts finally came to fruition in the creation of a secular United States of America separating church from state.

Colonial Christian forebears of today’s Christian Nationalists would be shocked and outraged that so many of their faith descendants have abandoned their witness. Shocked and outraged, too, would be the numerous Christians in the 1790s and early 1800s who — whether in agreement or not — wrote and talked about the founding of the United States as a secular nation in which church and state were separated.

Ignoring the voices of dissenting colonial Christians as well as the First Amendment’s clear separation of church and state, the Christian Nationalist fundraising letter instead reaches further back into history in search of somehow legitimizing the false claim of the Ten Commandments being the basis of American law and government.

“In 839 A.D.,” the fundraising letter states, “King Alfred compiled all known common laws into one book [the Legal Code of Alfred the Great]. The prefix began with the Ten Commandments and included the Mosaic law and Christian ethics throughout the known common laws of the time.”

The fundraising letter continues: “The ‘Code of Alfred’ became the basis for English common law, which, in turn, became the basis for the Magna Carta, both of which became the basis of American law and the underpinning of our U.S. Constitution.”

Not only is this false, it is sloppy falsehood.

In reality, King Alfred was not born until circa 849, a decade after the fundraising letter falsely claims he compiled his laws in 839. In fact, Alfred’s Legal Code was assembled in the early 890s.

A compilation of earlier Anglo-Saxon customary laws, the Legal Code was accompanied by a partial listing of the Ten Commandments as translated by Alfred. Commonly known in the Holy [Christian] Roman Empire to the East, Mosaic Law would have also been familiar to Alfred’s subjects. In the words of one historian of Alfred the Great, the Anglo-Saxon king “on the occasion of formulating a code of laws,” prefaced the volume by addressing “his statesmen and people in the tongue they could understand, the ancient commandments of God through Moses.”

Stretching to tie Alfred’s Legal Code to the founding of the United States, the Christian Nationalist fundraising letter states that the 9th century document “became the basis for English common law.” In reality, Alfred’s Legal Code made an early contribution to English common law, but did not – as the fundraising letter claims — become a straight line to the Magna Carta of the 13th century, thereafter traveling in a straight line to a supposedly Ten Commandments-influenced U.S. Constitution.

Examining the actual historical record, constitutional historian Steven K. Green — former AU legal director — writing for the Journal of Law and Religion, concludes that “Magna Carta’s influence on American constitutional development is tenuous at best.” Nor does the Magna Carta make any mention of biblical scripture or the Ten Commandments.

In short, Christian Nationalist leaders at multiple levels are clearly lying — in violation of the Ten Commandments’ prohibition of lying — when stating that the Ten Commandments are “the basis of American law and government.” And in violating biblical law, they reap great financial rewards from followers who happily send them money for spreading falsehoods about our nation’s history.

Extreme ironies aside, utterly unexplored in the fundraising letter is an actual historical connection between the biblical Ten Commandments and an entirely different era, a connection rarely if ever discussed by white Christian Nationalists – and for good reason.

Long before the biblical Pentateuch — the first five books of the Old Testament — was formally compiled in written form around the 6th century BCE, early Israelites, according to the Bible, were enslaved in Egypt during much of the 2nd millennium BCE. In Egypt they became familiar with Egyptian customs and religion.

Among the earliest compiled writings in Egypt were funerary texts, including a body of texts then known as the Spells of Coming Forth by Day. Today referred to as the Book of the Dead, it is “one of a series of manuals composed to assist the spirits of the elite dead to achieve and maintain a full afterlife,” in the words of Egyptologist Geraldine Pinch.

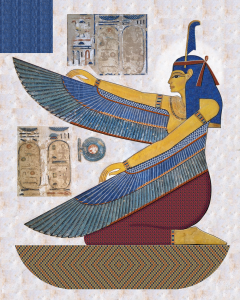

Polytheistic in nature, ancient Egyptian religion was, in later terminology, paganism. Included in the paganistic Book of the Dead were the 42 Laws of Maat, an Egyptian goddess representative of truth and wisdom. Consisting of principles for living a moral and just life, Maat’s laws centered on “I have not” declarations of innocence of harming the gods, fellow humans and oneself — including the avoidance of killing, stealing, disrespect, lying, cursing, deceitfulness, arrogance, adultery and evil at large.

Eventually the enslaved Israelites fled Egypt and sought their own lands. As they wandered about, they naturally began shaping their group identity from long-held religious and moral codes with which they were familiar. They adopted many ancient polytheistic/pagan religious stories, including creation and flood narratives, which they modified for their own emerging monotheistic faith.

A foremost example of the adoption of ancient religious and moral codes was the Israelites’ embrace of the Laws of Maat. According to the biblical account, Moses, born in Egypt, led the Israelites out of slavery and received the Ten Commandments from God. Although attributed to their monotheistic God, the majority of those commandments nonetheless incorporated many of the Laws of Maat. [For further explanation, see accompanying article on page 12.]

In time those Ten Commandments, and thus many of the laws of the goddess Maat, also became sacred to Christianity and Islam — but are absent from the Constitution of the United States of America.

Entirely avoiding the historical background of the Ten Commandments, the white Christian Nationalist fundraising letter that came my way ends with these words: “Thank you for your gift to uphold the Ten Commandments in America!”

Those words would have puzzled colonial Christian dissenters demanding church-state separation, America’s Enlightenment founders who enacted church-state separation, and late 18th and early 19th century Christians either celebrating or condemning America’s founding as a secular nation.

Puzzled, also, would have been the goddess Maat, ancient Egyptians and the ancient Israelites.