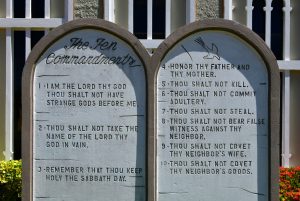

George Bernard Shaw is reputed to have quipped that America and England are two countries separated by a common language. When it comes to the Ten Commandments, Judaism and Christianity are two religions separated by a common text. The language suggested by Louisiana House Bill 71 to post the Ten Commandments in all public school classrooms, alas, is grossly prejudicial — against Christians.

First, a note about nomenclature. Since the Louisiana law uses the term “Ten Commandments,” so will I. But, grammatically speaking, working for six days a week is just as much a commandment as remembering or observing the Sabbath Day. (“Remembering” is found in Exodus, and “observing” is found in Deuteronomy. The Exodus version seemingly makes fewer specific behavioral claims. What is one to remember, for example, when one “remembers” the Alamo?) Although there is an unresolved Jewish dispute about the number of commandments in the verses from Exodus 20:1-14, Moses Maimonides (1138-1204), the greatest Jewish legal authority of his day, enumerated 14 distinct commandments in what our tradition refers to as the eseret had’varim, or “The Decalogue.” (“Decalogue” is the Greek for “ten statements,” as opposed to commandments.)

Whether “I YHWH, your God, who took you out of the land of Egypt” is understood as a preamble to the Ten Commandments or as an actual commandment, it is making an explicitly religious claim. Since it’s the only religious proclamation mandated to be on classroom walls, the law privileges that text. In the precedent that the Louisiana law leans on, Van Orden v. Perry (2005), Chief Justice William Rehnquist, writing for the majority, observes that in “our own Courtroom … Moses has stood [since 1935], holding two tablets [sic]… among other lawgivers in the south frieze” [of the Supreme Court Building]. School children outside of the Abrahamic faith communities don’t claim Moses as their own. Posting the Ten Commandments in public school classrooms is not very compassionate, although that’s the least of the problems with this law. The next verse offends far more people: by prohibiting the worship of gods other than YHWH, the verse in its historical context portrays Christians as idolaters. (Exodus 20:4 and Deuteronomy 5:7; the four-letter name of God is generally translated as “the Lord.”)

What happens when little Mary, or little Miriam, or little Muhammad, reads that commandment and asks their teacher about Jesus? How could Jesus have taken anybody out of the land of Egypt twelve hundred years before the Christian Bible says he was even born? As an academically trained theologian, I have an answer, but it’s complicated and confusing. I wouldn’t trust anyone not well trained in both Christian theology and the ancient history of the Near East to address that question, especially in a public school setting.

If the worship of Jesus is prohibited by this commandment to not worship gods other than YHWH, that’s a problem for Christians. If the worship of Jesus is not prohibited by this commandment, that’s a problem for everyone — especially Protestants — who imagines they can read and understand the Bible without some sort of explanatory apparatus. Without such an apparatus, the worship of Jesus certainly seems like the worship of a god other than YHWH.

Louisiana could avoid most students’ questions if they posted the Ten Commandments in the original Hebrew. In the Van Orden decision, Rehnquist notes that the language on Moses’ tablets is Hebrew. But if only a handful of students and teachers understand the Hebrew, that would defeat the purported moral purpose of the posters. (There are fewer than 15,000 Jews in Louisiana, and my experience suggests that not all American Jews are able to read and understand biblical Hebrew.) According to Rep. Dodie Horton (R), the Louisiana state representative who sponsored the legislation, the measure intends for “our children to look up and see what God says is right and what he says is wrong. … It doesn’t preach a certain religion, but it definitely shows what a moral code we all should live by is.”

Since that is the motivation, I understand why the specific text mandated by the bill relies on the King James translation and is heavily redacted. Thus, the students will not read that we are commanded to let our slaves rest on the Sabbath. Were the legislation to have retained that clause in the commandment to remember the Sabbath, some clever students might imagine that slavery is unobjectionable to God, since God nowhere objects to slavery. Furthermore, concerning the prohibition against coveting of one’s neighbor’s slave, the King James employs the euphemism of “manservant.” Such a delicately sanitized translation should mitigate embarrassing questions about slavery, a particularly sensitive topic in the state which saw one of largest slave rebellions in U.S. history — the Louisiana Slave Revolt of 1811.

Sometimes, however, those delicate and sanitized translations of the King James may put legislators in an awkward position. One of the prohibitions in the Ten Commandments is against murder. Murder is unauthorized killing. The 58 people on Louisiana’s death row have been found guilty of a capital crime, and their deaths are authorized by the state. Therefore, their deaths should not be considered murder. However, the King James translation reads, “Thou shall not kill.” Might the posting of the Ten Commandments, with the prohibition of killing, be grounds to appeal the death sentences of those 58 convicted criminals? How will the government justify violating one of the Ten Commandments?

Frankly, I am also concerned about the mental health of those children in these classrooms who, through no fault of their own, might not be able to honor their “father and mother.” How would an orphan, for whom the Bible has so much compassion, feel with that text on the wall of every classroom?

Even the prohibition against adultery is also not so simple. The Bible does not consider marriages between a man and multiple wives to be adulterous, although a woman having multiple husbands certainly is adultery. Some Muslim students in the classrooms may feel well represented by such a commandment, since they still share that definition of adultery; but others might be uncomfortable thinking that, in Rep. Horton’s words, this commandment “definitely shows what a moral code we all should live by is.”

As a rabbi, I do not want to see my fellow Americans turn away from the moral foundations of the Hebrew prophets upon which much of contemporary Christianity is built. As an American, I agree with our Founding Fathers that the best way to protect religion is to keep it out of the public square and certainly out of the public classroom. Louisiana Gov. Jeff Landry and advocates of this law are promoting an ancient legal code that very few can read and understand in its original context (as originalists claim to do). Moreover, their own Christian religious practice and morality are at odds with much that is found in a simple reading of that redacted translation.

I fear the consequences of Louisiana’s students reading the Ten Commandments without the benefit of a trained religious educator to help students understand the historical context and development of those laws. I fear that some will reject Christianity as a religion that seemingly worships a false god, condones slavery and polygamy and prohibits all killing. It would be wiser to render unto God what is God’s in a religious setting, and to render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s in the public square.

As Jesus said, you can’t serve two masters.

Shai Cherry is the Rabbi of Congregation Adath Jeshurun in Elkins Park, Pennsylvania, and the author of Torah through Time: Understanding Bible Commentary from the Rabbinic Period to Modern Times.